Leprosy destroyed Mohammed Umaru’s dreams.

“I wanted to be a teacher. Maybe even a professor. But everything changed,” Mr Umaru, who lives in a leprosy colony in Ebute Metta, Lagos State, said. “I completed secondary school in 1994. But this illness started around 1987, before I graduated.”

Across Nigeria, thousands of leprosy survivors and their children are trapped in the misery of poverty, neglect, stigmatisation and discrimination. Over 3,000 lepers in the country face daily battles with chronic illnesses, psychological trauma, and poverty.

With little or no access to healthcare, the women give birth at home, without medical supervision. Education is a distant dream – many children in leprosy colonies are out of school. To survive, parents beg for alms while their children hawk along dangerous roads, reflecting how society has turned its back on them.

Nigeria officially records at least 2,500 new leprosy cases annually. Over 400,000 people live with the long-term consequences of the disease in 61 settlements nationwide.

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is a chronic infectious condition caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. It primarily affects the skin, peripheral nerves, upper respiratory tract, and eyes.

The disease spreads through prolonged close contact with an untreated person, often via respiratory droplets like coughs or sneezes.

However, contrary to common belief, leprosy is not highly contagious and is curable, especially when treated early. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends a multi-drug therapy (MDT) regimen, which is supposed to be provided for free across many countries, including Nigeria.

Although early diagnosis and treatment can prevent lifelong disability, stigma, isolation, and poor access to healthcare leave many patients untreated, trapped in a cycle of preventable suffering.

When PREMIUM TIMES visited four colonies – Alheri in Abuja, Elega in Ogun State, and Ebute-Metta and Alaba Rago in Lagos, the daily fight for survival, dignity, and recognition was evident.

In the colonies, survival is both a physical and psychological battle. Sadly, Abuja, the country’s capital, and Lagos State, the commercial capital, arguably host the most poverty-stricken victims in their three leprosy colonies.

The colonies are built around dumpsites, and the inhabitants survive on hard-to-get, polluted and foul-smelling water, contributing to widespread cases of pneumonia, skin rashes and muscle diseases among residents. UNICEF reported in 2019 that Nigeria accounted for the highest number of global child pneumonia deaths.

Alaba Rago, Ebutte Metta

Over 2,000 lepers live in Alaba Rago, a densely populated slum and dumpsite in the Ojo Local Government Area of Lagos State. The settlement is not connected to electric power and gets its water from a single source – a borehole d in 2008. Families practice open defecation while pregnant women deliver babies at home, using unhealthy measures of delivery, because there is no public hospital in the area.

“We invite private doctors for serious cases, and we seek money through street begging to foot the bill,” said Umar Abdulrahim, an indigene of Kano State, at the Lagos colony.

Mr Abdulrahim, a father of eight, was a teacher in Kano for 10 years until he was retrenched in 1981 because of his illness.

In the Ebutte Metta settlement, where over 200 live in dilapidated structures, lepers face similar tribulation. Many are blind, many can’t walk, and only a few work.

Lepers, aged between 45 and 75 years, struggle to provide for their children, forcing them into street begging.

After graduating from secondary school, Mr Umaru enrolled in a college of education. But leprosy and society’s rejection ended that path. By 2000, he had arrived in Lagos, forced to beg to survive. He lives in the Ebute Metta settlement with his wife and seven children.

Inside the settlement, the struggles run deeper. Toilets are few and often damaged. During the rainy season, the soakaways overflow, spreading filth and disease. Elderly residents, some in their 70s, are forced to crawl or depend on others to relieve themselves. Children bathe in open spaces—some wander off and never return, lost to the streets of Lagos.

“There’s no system here,” Ahmad Abubakar, the community leader, explained. “If someone can help you to the toilet, fine. If not, you crawl. This is our reality.”

After living for decades in Lagos, many of the inhabitants feel abandoned. “The government helped us back in the day. During the military era, food came monthly. Now, we wait six or seven months, and nothing happens. We’re forgotten,” Mr Abubakar said.

Built in 1997 for lepers displaced from Kano, the compound once symbolised relief. But now, it is crumbly from neglect. The walls are cracked, the roofs leak, and government support has dried up.

“If they can fix our buildings and support our children’s schooling, that would change everything,” a woman said in Hausa, clutching her infant. “We just want to live with dignity.”

Why Colonies Exist, Persist

Historically, leprosy colonies were established to isolate infected individuals and prevent the spread of the disease. Colonial governments and early public health authorities often forced lepers into remote, self-contained settlements to separate them from society.

However, modern medicine no longer justifies this segregation. Experts and international health agencies, including WHO and The Leprosy Mission, argue that isolation-based approaches violate human rights and reinforce damaging stigma. Instead, they advocate for community-based care, reintegration, and access to quality healthcare and education.

Despite this, many Nigerian colonies have remained in existence, some for over 60 years, due to weak policies, lingering stigma, lack of rehabilitation plans, and failed reintegration.

Education, a universal cry in settlements

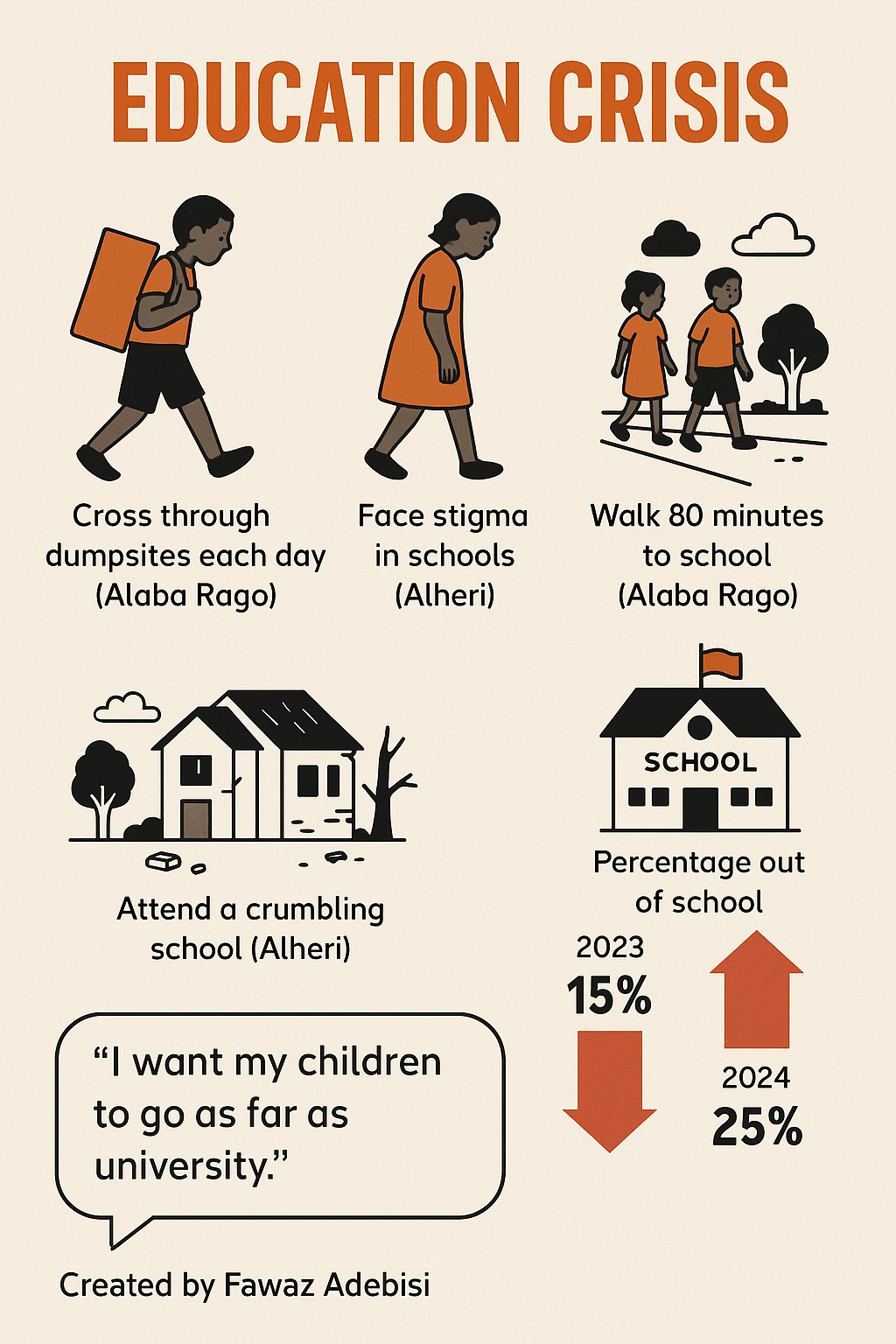

In the Ogun State and Abuja settlements, lepers want education for their children. Their struggle to support their children’s education is seen in many out-of-school children in the colonies.

Although Elega and Ebutte Metta colonies have accessible public primary schools, the children often do not proceed to secondary school for financial reasons.

“We are struggling to survive, so we can’t fund their education to those levels,” Folorunsho Lukman, the secretary of the Elega leprosy colony, said.

Mr Abubakar said his children attend a public school, where his first child was preparing for the final junior secondary school exams after the Salah holiday. But he still needs assistance. “I want the government to support their education. I couldn’t finish my own schooling, but I want all my children to go as far as university,” he said.

The children in Alaba Rago walk 80 minutes to the town and still get discriminated against in school because of the condition of their parents.

“They attend Ajegunle Government Primary School. However, not all our children attend because we face a lot of stigmatisation. Some children are mocked by other children. This affects them emotionally. They stop attending school out of shame, even though they were born healthy. We try to comfort and encourage them, reminding them that education is their future, even after we’re gone,” another resident said bitterly.

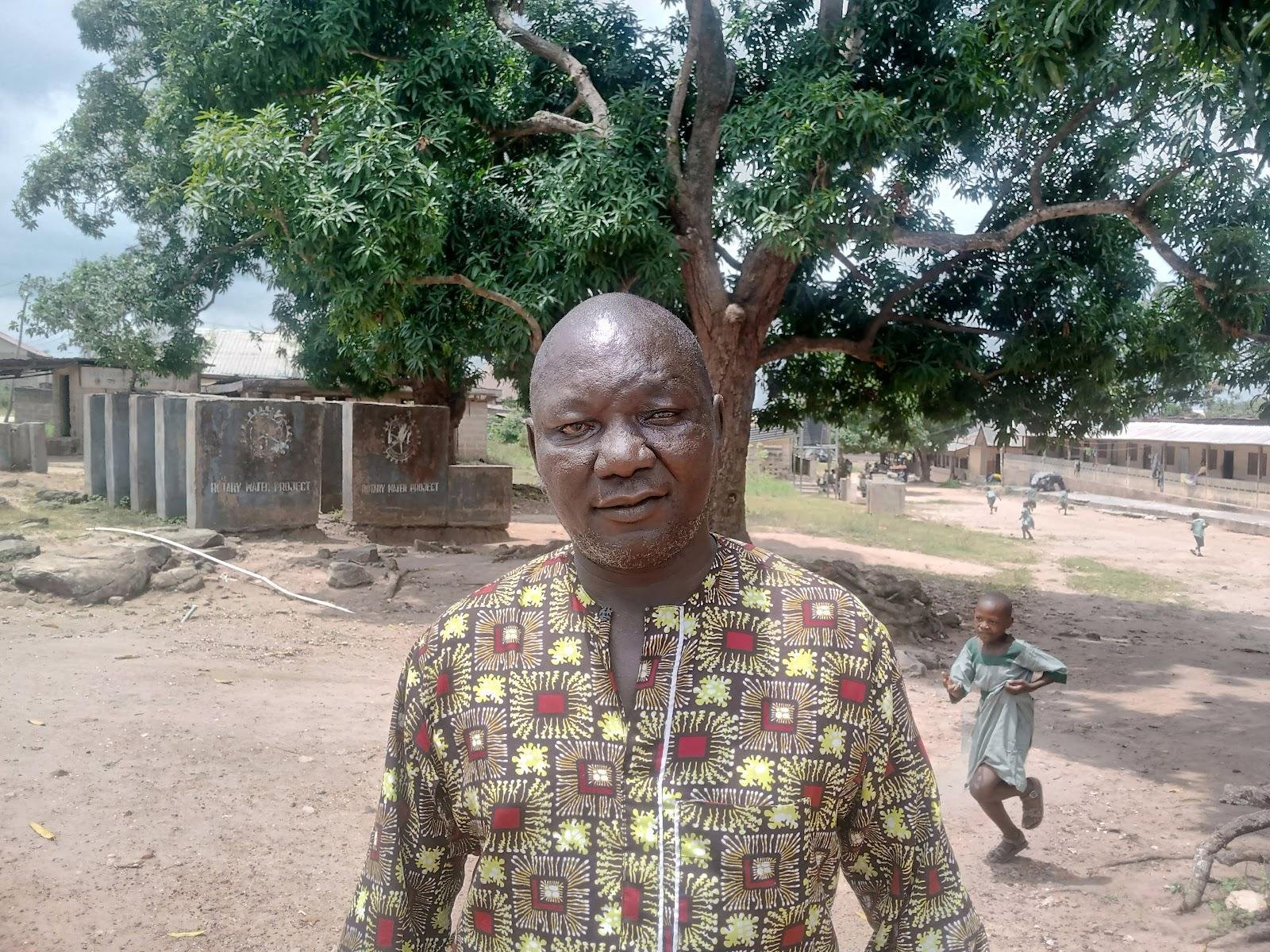

At the Alheri public school, only one of the five buildings is in a good state.

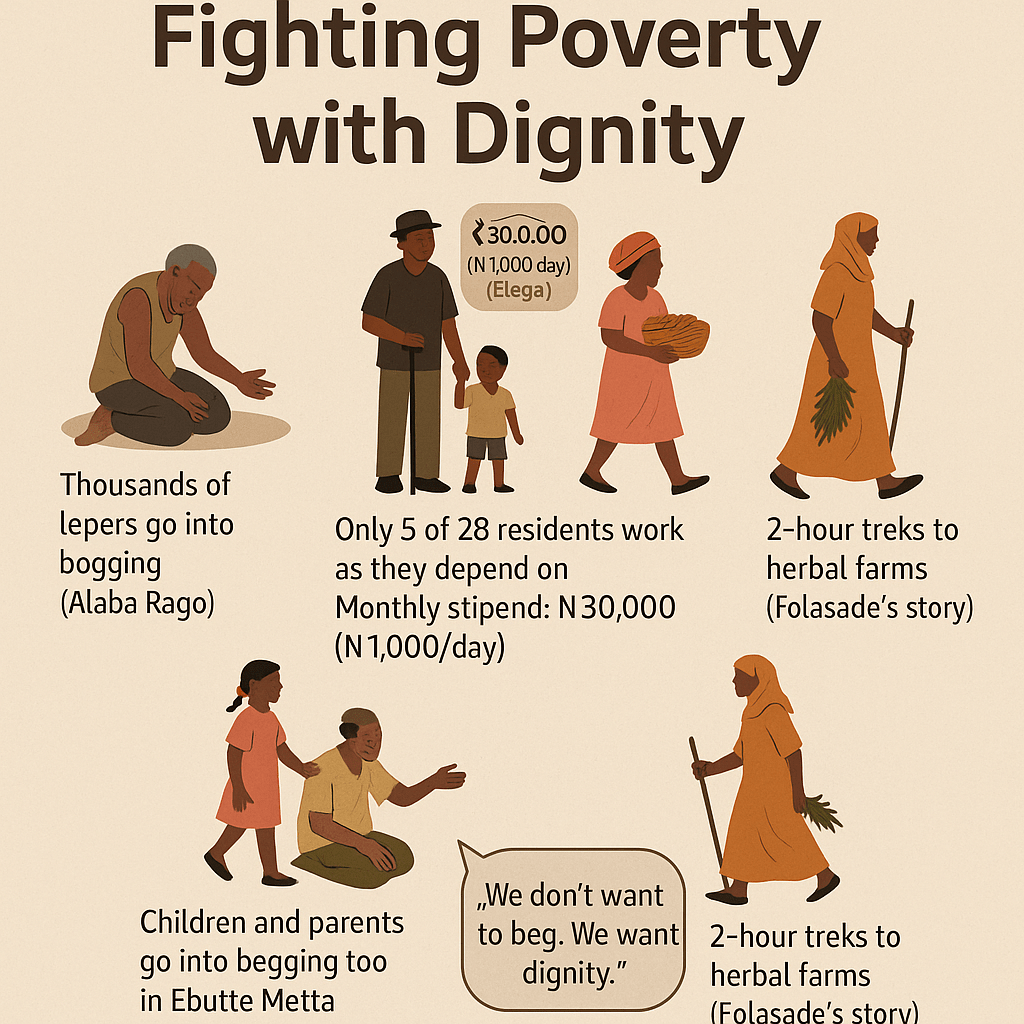

Poverty in the colonies

Ogun lepers appear to be better off. Operating a “no leper must beg” policy, they work hard to feed themselves and those who cannot work stay home.

“None of our members can go out begging, because we want our dignity to be there,” Jimoh Hammed, the chairman of the Elega Leprosy Settlement, said.

Despite the policy, only five of the 28 survivors have work.

Besides Mr Hammed and Mr Lukman, who drive taxis for a living, the other three who work sell herbs.

Among those who work is Folasade Olanrewaju, a mother of three battling a persistent leg ache. Her only child, who is old enough to help her, is in school. “I give her ₦1,500 daily for school, and she eats when she returns,” Mrs Olanrewaju said, her eyes dimmed by years of struggle. “I depend on selling herbs. I trek to the farm where I get them and struggle so my daughters won’t beg or become wayward.”

“A trip takes me two hours. Sometimes, I rest more than twice on the road. I’ve been doing this for 20 years, even with my bad leg. I go to the market twice a week.”

Mrs Olanrewaju spends over ₦90,000 per term on her child in school. “I’m using only one leg. If I can find something I can do without stressing my leg, I’d take it,” she said.

Nearby, Idowu Abudu, known in the area as Iya Eleko, has lived at Elega for over two decades. “Before I came here, I was making eko (corn pap),” she recalled. “But when I started making pap here, smoke from the fire affected my eyes and blurred my vision.”

“But I can’t stop. I have five children to cater for.” She supplements her earnings by selling herbs.

Through their pain, these women, and the few others still able to work, support others who can’t, ensuring no one goes out to beg.

The children also hawk to support their parents, selling wara (local cheese), doughnuts and other snacks. However, in other settlements like Ebute Metta and Alaba Rago, children and parents engage in street begging.

To support the lepers in its Elega colony, the Ogun State Government gives each adult leper ₦30,000 monthly, raising the stipend from ₦10,000 in March 2024. However, many of them said the allowance is inadequate because they have families to take care of.

Healthcare in colonies

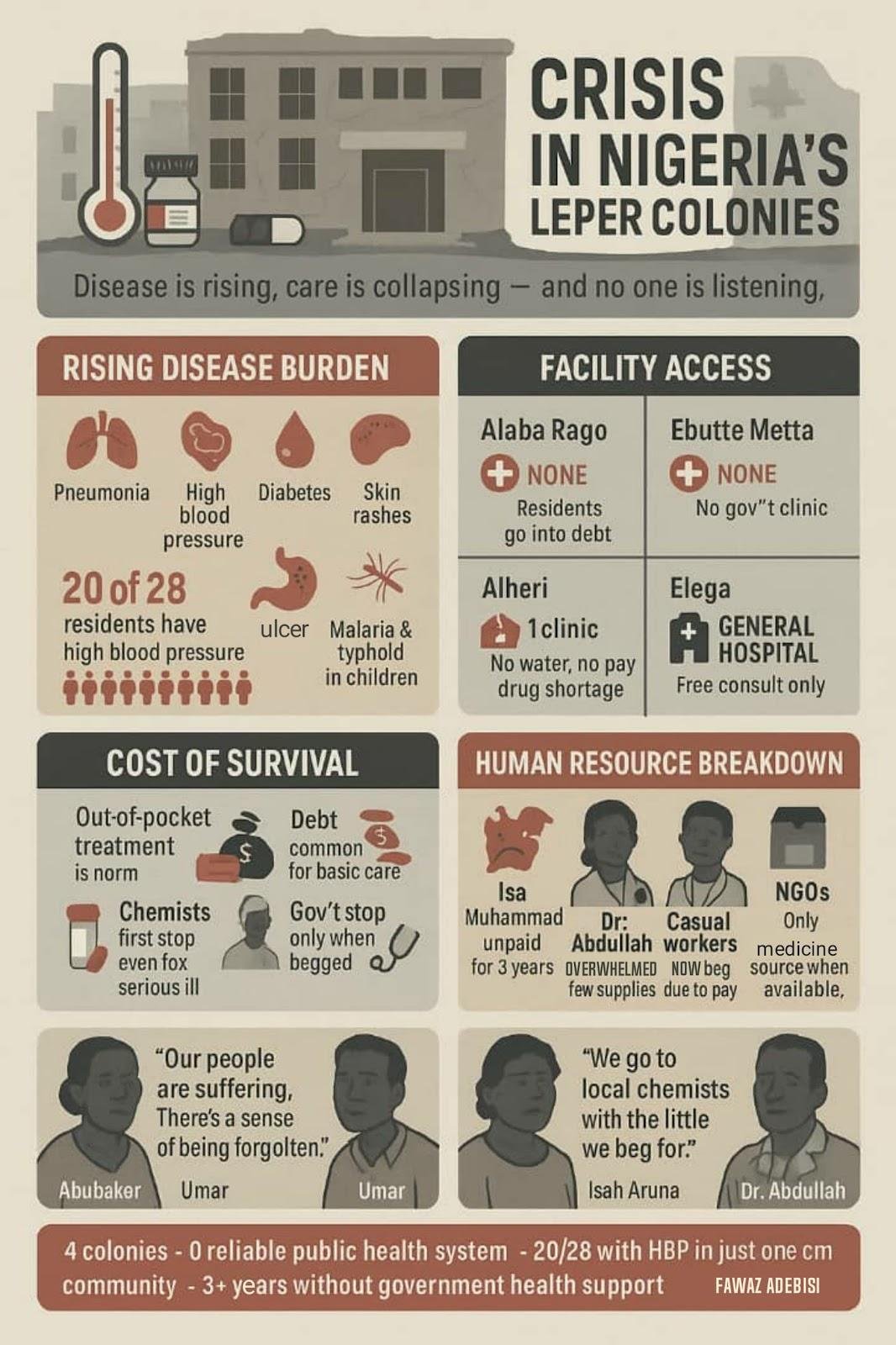

Cases of skin rashes, ulcers, pneumonia, High Blood Pressure (HBP), muscle disease, cough, diabetes, among many other diseases are high in the four colonies visited by this reporter.

Yet, Alaba Rago and Ebutte Metta colonies in Lagos do not have public health care facilities. The residents go to the nearest primary health centre for treatment or embark on self-medication.

“We lack many things and feel forgotten. Our challenges are many, and we need help with food, clothing, education, and health care. Our people are suffering,” said Mr Abubakar.

“We don’t have access to healthcare,” Mr Umaru said. If someone falls sick, we go to the local chemist and buy medicine with the little we beg for by the roadside. If the illness is serious, we sometimes report to the local government, and we might get assistance for a day or two.”

However, in the Elega colony in Ogun, 20 of the 28 of them were diagnosed with high blood pressure. Ironically, a general hospital sits in the middle of the settlement. Yet, survivors are left without drugs or access to free health care.

Many lepers also suffer from diabetes, while their children constantly fight malaria and typhoid, according to a health officer at the general hospital who pleaded anonymity for fear of victimisation.

“They have to pay for other services, or we prescribe drugs for them to buy outside,” said the officer, adding that “the only thing we do for free is listen to their complaints.”

The situation is no better at the Alheri colony in Abuja. The only health centre in the area is rapidly deteriorating. Skin rashes, pneumonia, and muscle disease are rising, yet the centre lacks basic medical supplies.

Isah Aruna, a middle-aged resident of Alheri, shows his scars with trembling fingers. “See my body; it itches badly, and when I scratch it, blood comes out,” he said, his voice lined with pain.

The burden of care is left to overstretched volunteers and underpaid workers, like Salisu Aruna, a doctor. “Any doctor that comes here must be devoted to them and try to get them drugs from any organisation that comes here,” he explained. “Some NGOs have brought medicines, but they’ve finished. We keep reminding them anytime they come again.”

One of those unpaid workers is Isa Muhammad, a 50-year-old who hasn’t been paid in three years. “For years, we’ve not gotten help from the government,” he said.

Hussein Shinkoso, 52, a carpenter and clinic staff member, shares a similar story. “I live here with my family. The Leprosy Mission Nigeria used to give us stipends, but that has stopped. It’s been three years since I last received anything from the government. If they can give us grinding machines, we can at least make a living.”

Others like Mallam Adamu, an elderly ulcer patient, express needs beyond medicine. “It’s been a long time since we got shoes. We need support in that regard, too,” he said.

NGOs Come to Aid

Where state institutions have failed, NGOs have stepped in, albeit with limited and intermittent resources.

At the Elega colony, Mr Lukman expressed cautious gratitude. “We thank the local organisations that support us, like the Lions Club, Rotary Club, Mace Club, and many NGOs,” he said. “They visit us often, giving us food, water, and financial assistance. Some even helped us power our water systems with solar energy.”

Also in Abuja, the Leprosy Mission Nigeria, FCT branch, provides constant support for lepers, as testified by the residents of the Alheri colony.

The mission’s programme officer, David Aire, described their ongoing support efforts, saying, “This community is one of our project locations.”

“We’ve been able to treat and cure some individuals and have provided footwear, protective wear, and crutches to those who lost limbs or fingers,” he said.

Things could get worse

Health professionals decry the conditions in Nigeria’s leprosy colonies, warning of dire health consequences if systemic neglect continues. With many residents suffering from chronic illnesses such as hypertension, ulcers, pneumonia, and diabetes, the collapse of regular access to medication and medical personnel poses an immediate threat. In Elega, for example, 20 of 28 lepers live with high blood pressure, yet have to pay out-of-pocket for treatment despite a state hospital within walking distance.

A March 2025 investigation by Reuters revealed that Nigeria’s multi-drug therapy (MDT) stockpile, the global standard for treating leprosy, ran dry for almost a year, leaving thousands untreated.

Medical staff at ERCC Hospital in Nasarawa lamented the resulting complications, including amputations and irreversible nerve damage. “If fingers are lost, where will you get them back?” one health worker asked, highlighting the cost of delayed care.

Doctors working within the settlements report mounting pressure and dwindling morale. At Alheri, the sole clinic is crumbling and without water, with unpaid staff struggling to respond to a rise in malaria and pneumonia among both adults and children.

Muhammed Abdullah, a full-time doctor, describes a system teetering on collapse. “The majority of the cases are malaria and pneumonia,” he said. “Some come for hypertension or ulcers. The cases that are beyond us, we refer them to Kwali General Hospital.”

But the clinic is struggling. “We have challenges with drugs. We need the government to provide support. It’s only NGOs that assist. There is no water, and the facility needs repairs. And we haven’t received any government support in three years,” Mr Abdullah lamented.

Even the casual workers have been left without pay. “Some of them now neglect their duty. That’s why, at times, you see the clinic is dirty,” he added. “These people feed their families from what they earn here. Now, they’re forced to beg to survive.”

The WHO’s Global Leprosy Strategy, 2021–2030, calls for ending leprosy as a public health problem by focusing on early detection, zero discrimination, and zero disability. It promotes integrating patients into normal society and discourages the use of colonies unless strictly temporary.

According to a 2022 UN Human Rights report, forced isolation of persons affected by leprosy “violates international human rights obligations” and urges countries to “dismantle colonies where possible and invest in inclusive social protection programmes.”

International experts have also echoed these concerns. The UN Special Rapporteur on leprosy has repeatedly warned that poor healthcare infrastructure in such communities threatens not only human dignity but also public health security. Without swift intervention, doctors and health experts fear that curable conditions will continue to cause permanent disabilities and deaths in these neglected corners of Nigeria.

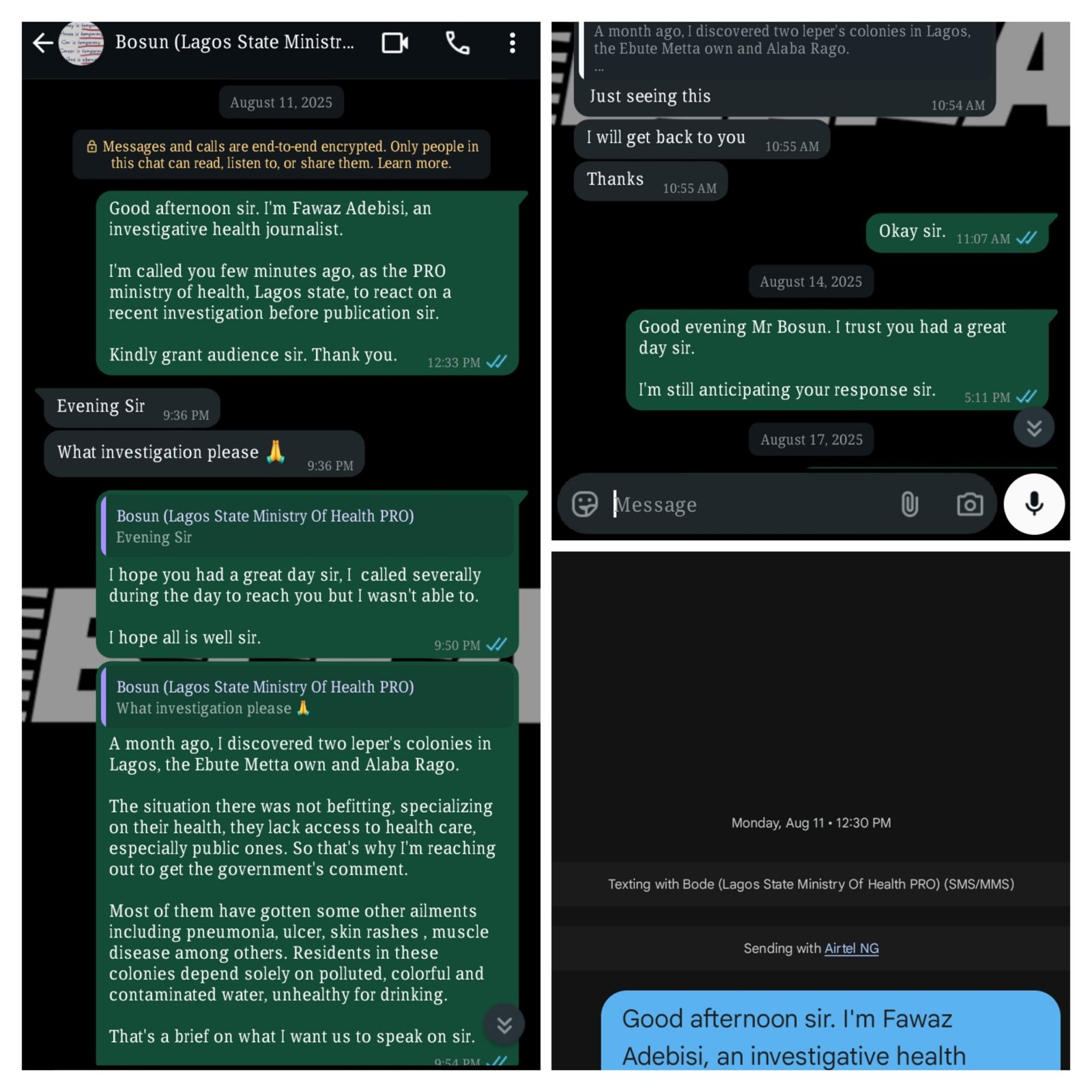

Government keeps mum

The Ogun State and Lagos State governments refused to react to the state of the colonies in their states.

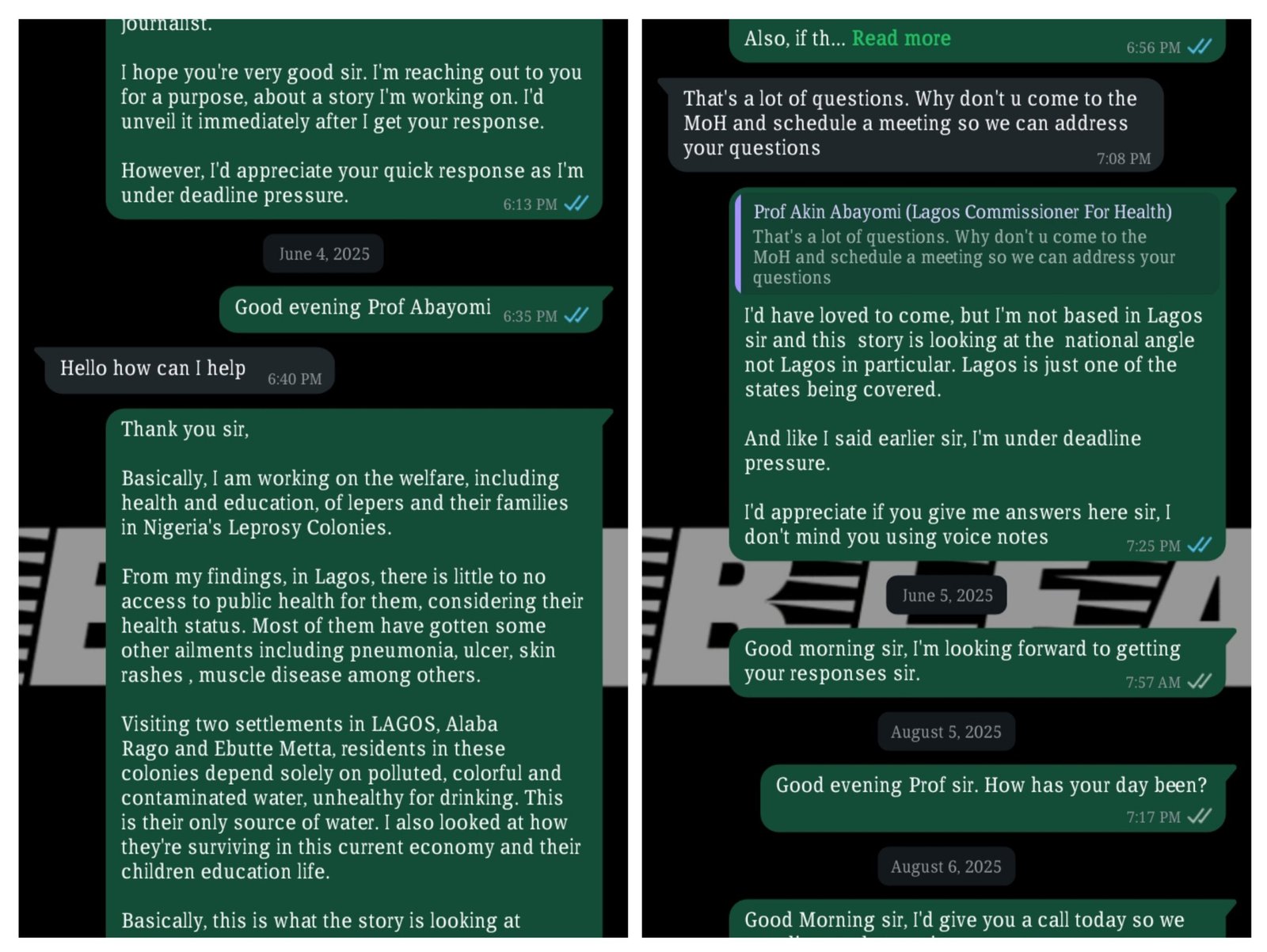

When contacted, the Lagos State Commissioner of Health, Akin Abayomi, requested a one-on-one interview, which was not realisable for this reporter due to the long distance. After explaining the situation and urgency of this report, Mr Abayomi continuously ignored other messages sent to him by the reporter.

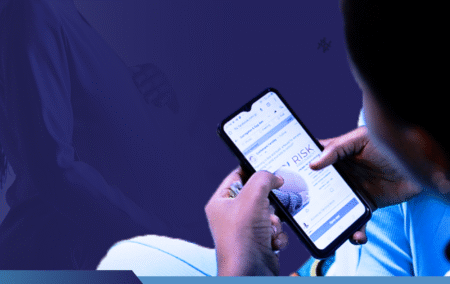

This reporter also reached out to the Director of Public Affairs at the Lagos State Ministry of Health, Olatunbosun Ogunbanwo, who, for up to a month, did not give an audience after listening to the synopsis of the story. Calls and text messages were sent, but not responded to.

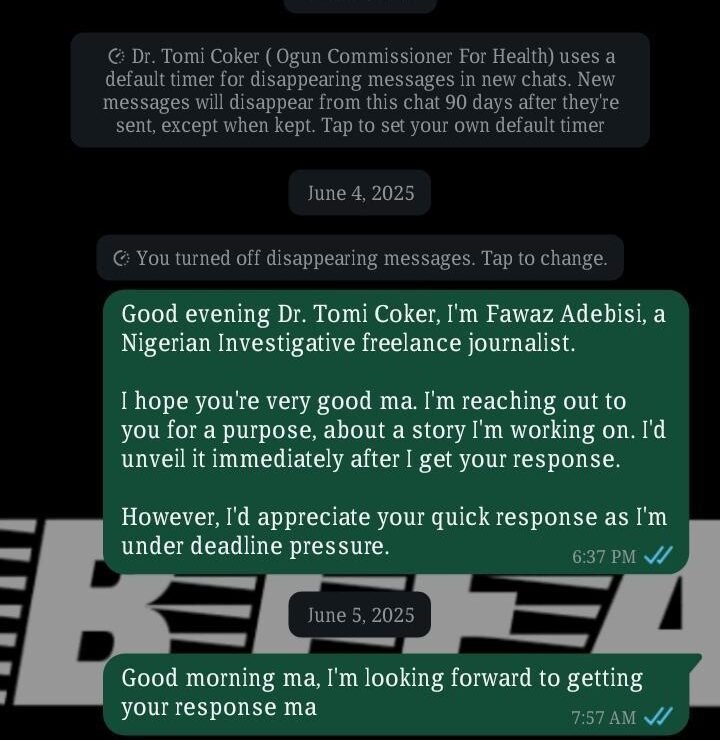

Also, the Ogun State Commissioner of Health, Tomi Coker, did not respond to the messages sent to her via WhatsApp or SMS.

At the federal health ministry, this reporter submitted a letter requesting an interview to discuss the situation at the Alheri colony.

For over a month, this reporter followed up with visits and phone calls to the ministry; the only response this reporter got was a call from an official at the ministry, saying, “We’re working on it, we’d get back to you very soon.” The official refused to mention his name.

This reporter also reached out to the Special Assistant to the Mandate Secretary, Health and Environmental Service Secretariat, on Media, Bola Ajao, who provided the contact of Dan Gadzama, the director of Public Health, FCT, and said he was the appropriate person to speak to.

READ ALSO: Bauchi uncovers 100 ghost workers in health sector, vows sanctions

When contacted, Mr Gadzama told the reporter he has no order to reveal any information yet. He simply said, “Work is going on and we will get back to you soon.”

He later sent a text message, “Thank you for that memo on the Lepers community. God bless you and your family for speaking out for the poor and vulnerable.”

The silence across all levels of government, Lagos, Ogun, Abuja, and beyond, paints a grim picture. For thousands living in the leprosy colonies, the hope for dignity, healthcare, and humane treatment remains a dream.

Read the full article here